The Prides and Perils of Open (Source) Diplomacy

Decades of experience in giving speeches, keynotes, and running workshops. Done!

Days of scripting and slide-making, and targeting a highly technical COSCUP audience. Done!

Seventeen hours of a flight to Shanghai followed by a maglev train into the city. Done!

An hour-long presentation about open source education, careers, and opportunities. Done!

Breathe. Now, it was time for the Q&A where the first question from the audience was totally unexpected:

“Why does LPI’s Marketplace have Taiwan listed as a country?”

It took me a moment to collect myself, but the answer came quickly: neutrality, one of the core principles of Linux Professional Institute (LPI).

One of the things that has always distinguished LPI from other IT education and certification programs has been neutrality, baked into our mission from day one. No Linux distribution, no vendor, no method of training was to be preferred over others. As we go into our third decade, not only has our commitment to neutrality not diminished, it is more important than ever.

LPI’s recently released BSD Specialist certification program, the result of years of collaboration with the original BSD Certification Group, represents neutrality of open source operating systems. That, and our DevOps programs, takes us beyond our purely-Linux roots, along with other programs under development. Lately, an even more intriguing form of neutrality has become an issue, whether or not we wanted it, that being political neutrality.

The unexpected question posed that day at East China Normal University extracted an answer that was itself quite natural for us. Besides all the other forms of neutrality to which LPI adheres, political neutrality is just as important, if not as high profile.

The TL:DR version of this neutrality is that LPI will offer its programs anywhere we are welcomed and legally allowed to do so. This cuts across political systems, transparency, or human-rights ratings, or any other criteria that won’t put our people in danger. We try to avoid inter-country conflict, working with anyone who wants to work with us. When it comes to naming — the source of the Shanghai complaint — we prefer to use the terms that people use to define themselves, while recognizing that even names can cause big difficulties. Sometimes no matter what we do, someone is going to be offended, but our default is to let our community members self-identify.

It’s been a fortunate history that LPI’s legal head office is in Canada, a country with few international hostilities and many free trade agreements. There are very few countries on which Canada has sanctions, and even on that list, most are against specific people or industries rather than the whole country. Consequently, we are able to operate in many places that some would consider controversial, the exam labs recently held in Cuba being a perfect example.

LPI has always been about open source, open technology, and people who either work with it or want to work with it. We know that not everyone agrees with the politics of their governments, and even if they do that shouldn’t get in the way of our mission. We believe that open source and open standards (and more openness in general, including more use of Creative Commons) are globally beneficial, directly to practitioners, and indirectly to the societies in which they live. If we and our community are given an opportunity to spread the use of open source and help people make careers using it, we’ll take that opportunity wherever it happens. We’re eager to make partnerships, talk to user groups, and participate in relevant events anywhere we’re welcome (subject to available resources and planning, of course).

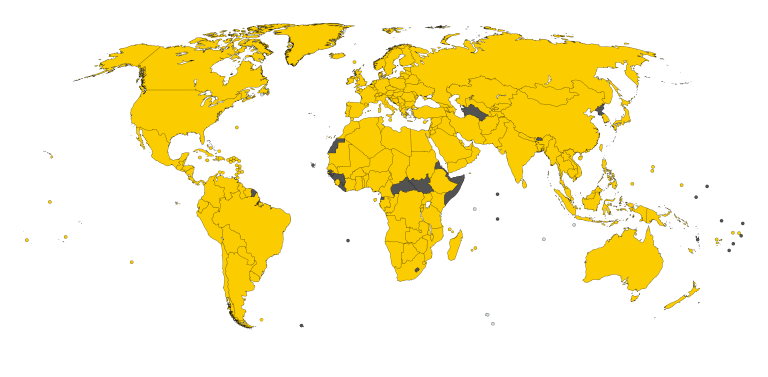

One of our great sources of pride, that makes it into almost every new conversation and presentation, is the fact that there are people who have received LPI certifications in more than 180 countries (see the map above). That includes Israel and Iran, China and [whatever name for Taiwan you prefer to use], and a whole bunch of hostile neighbours and unpopular governments.

We are not trying to solve world peace, nor are we equipped to do so. In fact, we have been accused, on occasion, of endorsing unliked regimes by working in their countries. But our focus is sharply on the people who love technology and want to make a life working with it. If we can bring them a common passion for software openness, and bring that message home, I think we’re doing some Good.

If you would like to get involved in our global community to help make that happen, please write me at eleibovitch@lpi.org, or find me by name on Twitter, Signal, Telegram, Wechat, Hangouts, Slack, LinkedIn, Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype or even Wikipedia’s new platform, WT:Social. Talking to friends around the world means I don’t have the luxury of just one or two chat platforms. 🙂